INHABITTING MANHATTAN SCHISTS

Summer 2025

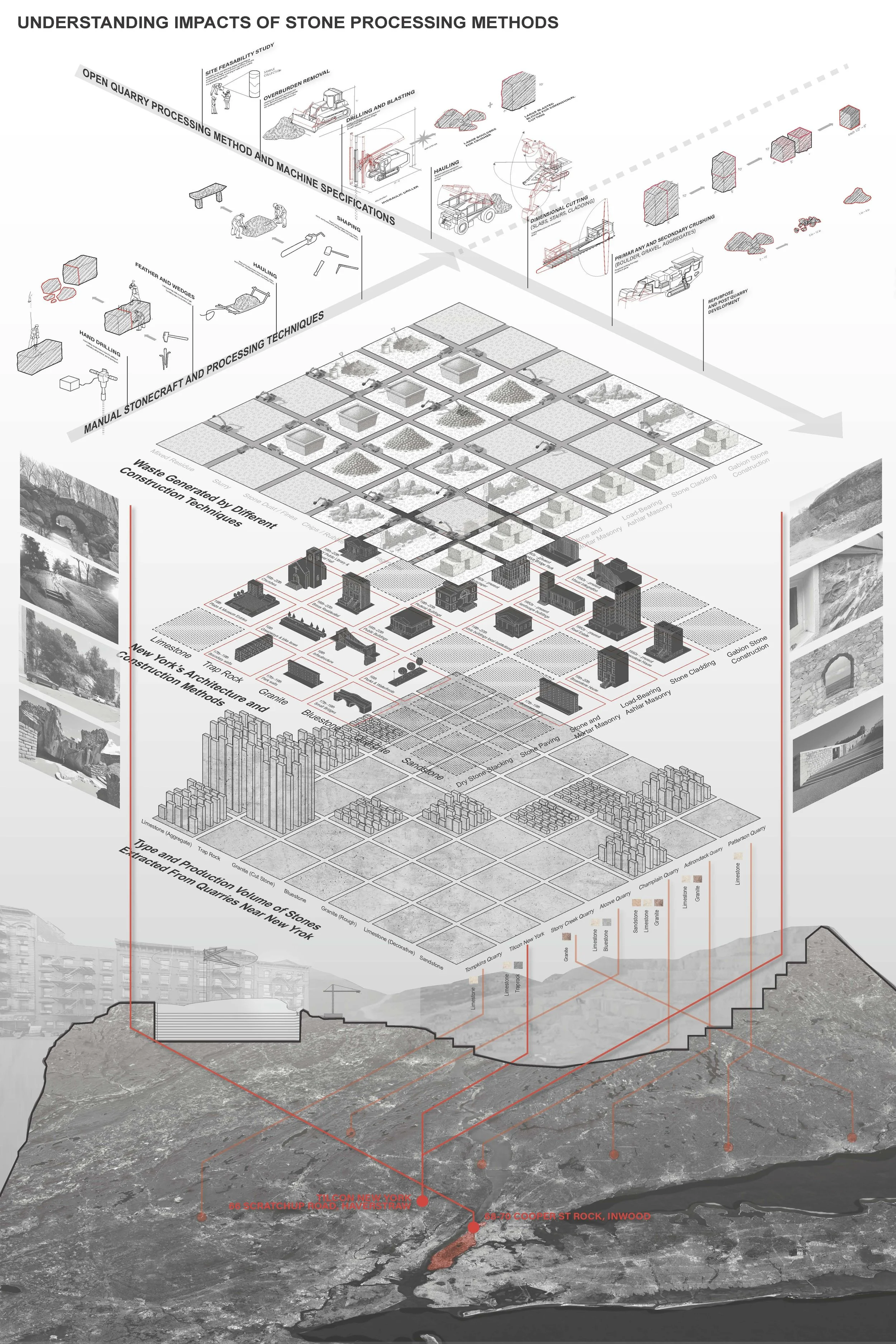

RESEARCH: STONE PROCESSES

Our research begins with an inquiry into the landscapes and operations of quarries surrounding New York City. By examining the types, machinery, and outputs of these extraction sites, the research process aims to understand stone extraction’s broader implications on the built environment, the disruptions they cause, the waste they generate, and the potentials for reuse embedded within their processes. This investigative framework serves as a foundation for the design approaches, each interpreting the act of quarrying as both a material and spatial condition.

Process Analysis: The Language of Extraction

A typical open-pit quarry follows a systematic sequence of site evaluation, removal of overburden, drilling and blasting, and transport for crushing or dimensional cutting. Within the New York context, stone is most often processed into cladding slabs, an architectural finish detached from its geological origins.

Each stage of the quarrying process was analyzed and mapped through levels of noise, displacement, and environmental impact. This research led to an exploration of manual and mobile alternatives, such as feather and wedge splitting, enabling smaller-scale and low-impact forms of extraction. These methods yield irregular sizes and rhythms of stone, introducing a tectonic language grounded in restraint, precision, and locality.

Geology of the City: Manhattan Schists

The distribution of this schist has influenced the city’s growth. Skyscrapers cluster in areas where the rock lies close to the surface, such as Midtown and Lower Manhattan, while neighborhoods built on softer soils remain lower in height. Historically, schist was quarried locally for retaining walls, arches, and bridges, most visibly in Central Park, where its rugged texture was celebrated as part of the park’s landscape. Over time, industrial construction replaced local stonework with imported materials, and the schist receded into the background of the city’s collective memory. This project reexamines that material, treating it as both a geological foundation and a cultural artifact that continues to shape New York’s identity.

Site photo: Cooper Street Rock

Site PO

REDISCOVERING SCHIST: COOPER STREET ROCK

The project reexamines the use of stone as an exterior cladding, questioning its detachment from origin and meaning in contemporary construction. While New York City once relied on local quarries for its building materials, much of its current stone is imported from across the world for its perceived luxury and exotic appeal. This global dependence has overshadowed the Manhattan schist, a material that is both abundant and deeply rooted in the city’s geological and cultural fabric. Schist structures appear throughout New York’s parks and infrastructure, from the arches and retaining walls of Central Park to the bridges and paths that carve through its landscapes. These examples reveal how the city once engaged directly with its ground, shaping and inhabiting the stone rather than concealing it.

Site

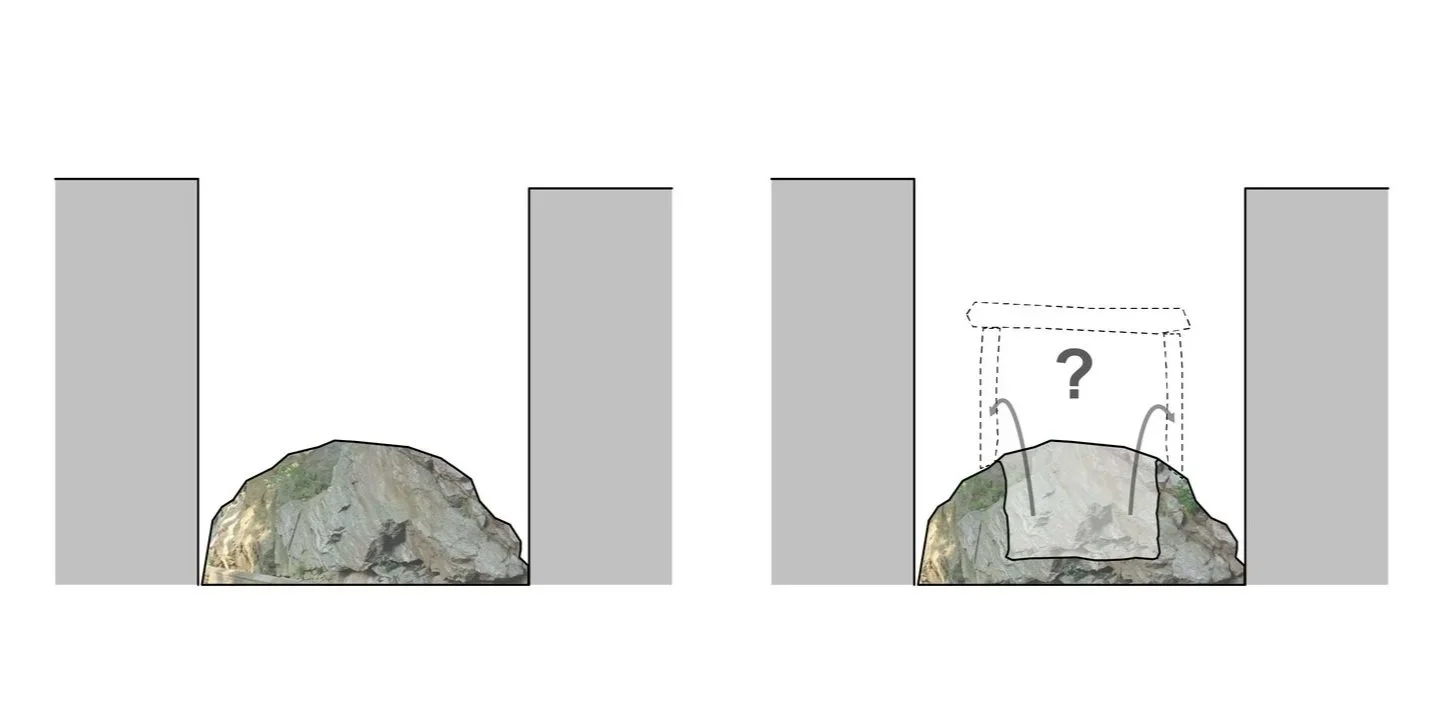

Scattered across the Manhattan grid are natural schist outcrops that have remained undeveloped for centuries, often dismissed as obstacles to construction. The project reinterprets these outcrops as on-site resources and spatial opportunities, proposing a model where extraction and inhabitation occur simultaneously. The selected site Cooper Street Rock, a long-standing outcrop once accompanied by a community garden, carries a layered social history. For decades, residents cultivated and cared for the space, transforming its base into a small garden that softened the street and provided a shared refuge. In recent years, however, rezoning designated the plot for redevelopment, the garden was cleared, and the site was fenced off from public access.

Approach

The design responds by reopening the outcrop to the neighborhood, using its own material to construct new space within it. Stone extracted from the site becomes both the medium of construction and the memory of the process, forming a neighborhood living room embedded in rock. The project explores how architecture can operate within geological and social continuity, using low-impact quarrying and on-site reuse to create a place that restores access, honors community history, and invites people once again to inhabit the stone.

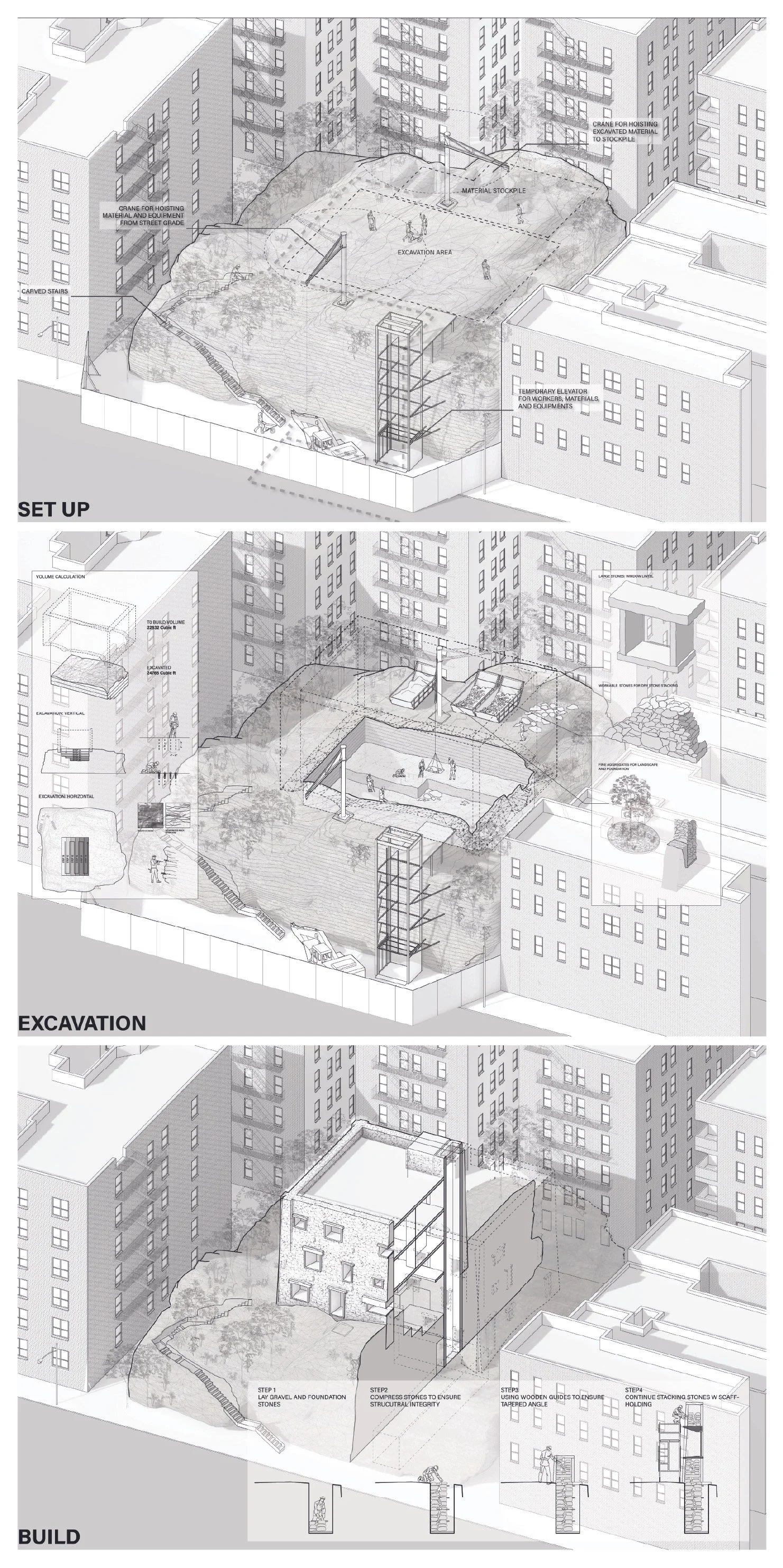

CONSTRUCTION SEQUENCE: EXCAVATION TO ASSEMBLY

Preparation

The process begins by establishing access and circulation across the outcrop. Pathways are carved to guide movement for both construction workers and future visitors, while temporary cranes, scaffolding, and lifts connect the street level to the elevated terrain. These temporary structures allow material and equipment to move efficiently and safely. Zones for material storage and sorting are defined early, organizing stones by size and use to streamline the later stages of construction. The preparation stage sets the foundation for a gradual and continuous transformation rather than a single act of erasure.

Excavation

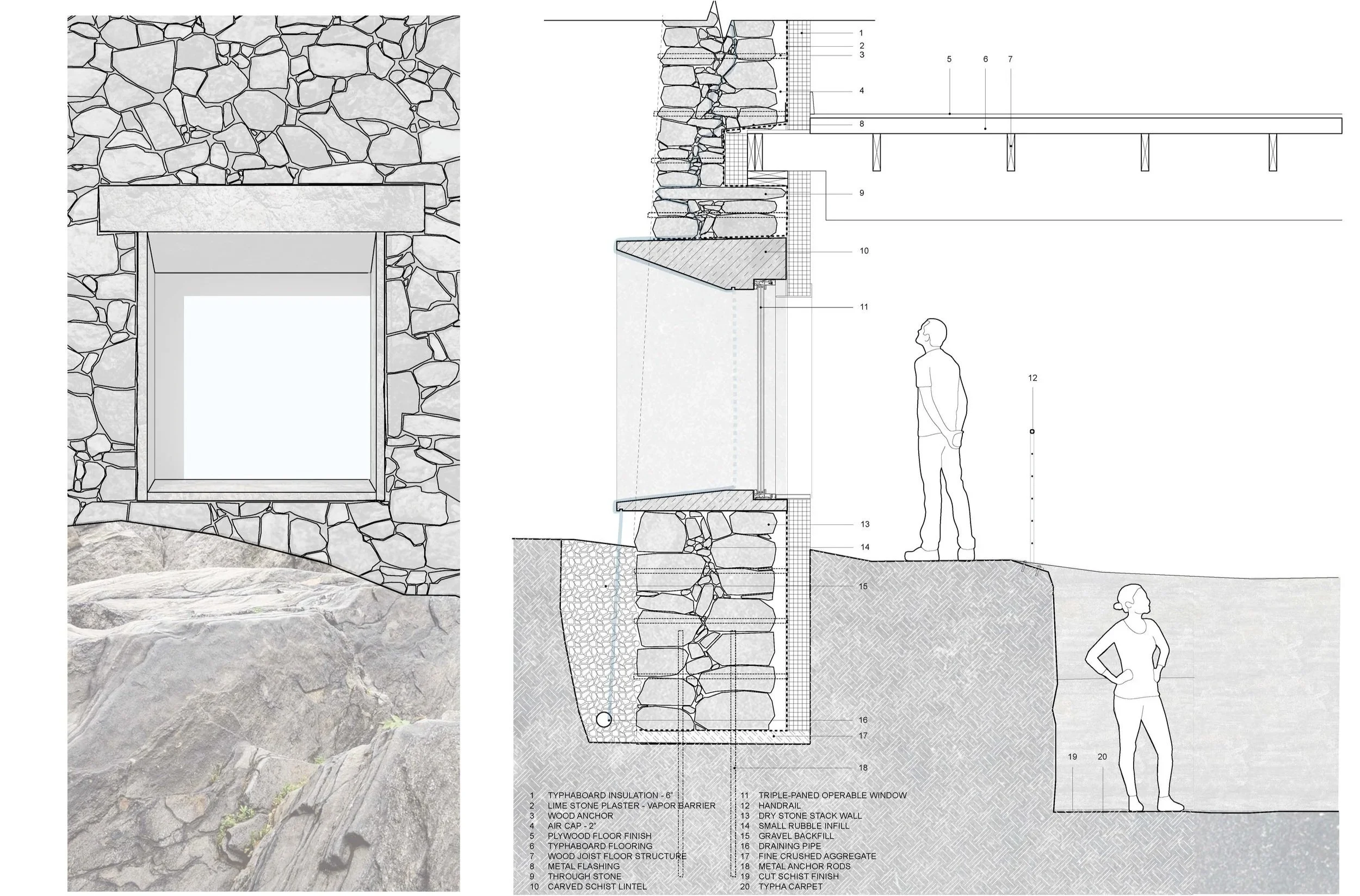

Extraction follows the natural grain and stratification of the schist. Vertical cuts between three and six feet are combined with horizontal breaks to control the direction and stability of the process. Instead of large machinery or blasting, smaller-scale tools such as feather and wedge systems and handheld saws are used to minimize noise and vibration. This slower method preserves the integrity of the site and maintains a close relationship with the material. Stones are sorted directly on-site: small fragments become aggregates, mid-sized stones are reserved for dry stacking, and large blocks are selected for foundations and lintels.

Building

Construction proceeds with the immediate reuse of excavated material. Drystone load-bearing walls rise from the same rock that once anchored the site, relying on gravity and precision fitting rather than mortar. Larger stones are carved into lintels, thresholds, and furniture pieces, while smaller pieces fill cavities within the walls to stabilize and insulate the structure. The building grows from the rhythm of extraction itself, its textures and proportions shaped by the tools and techniques used to form it. The result is a structure that carries the memory of its making, blurring the boundary between excavation and inhabitation.

The resulting structure operates as a geological extension of the outcrop, merging built form and terrain into a single continuous body. The mass of schist stabilizes temperature throughout the year, storing solar heat during winter days and releasing it gradually at night, while its density delays heat transfer in summer, keeping the interior cool and temperate. Carefully positioned openings channel light deep into the stone, revealing its mineral variations and layered surfaces, allowing the interior to shift in tone and warmth as the day progresses. The building becomes an instrument for observing time, its walls recording subtle changes in temperature, humidity, and light across the seasons. Through a commitment to low-tech and non-extractive methods, the project advances an endogenous approach to architecture, one that grows from the geological and cultural strata of New York itself. Schist, long overlooked yet omnipresent beneath the city, re-emerges as both structure and symbol, reconnecting contemporary construction with its material origins. The work proposes that building is not an act of imposition but of listening and adaptation, aligning human rhythms with the slower temporalities of stone. By intertwining geological memory and urban life, the project envisions a mode of making that is both restorative and enduring, allowing the city’s deep time to remain visible within its evolving future.